Men: Urethral Stricture Disease and urethral reconstruction

Urethral Stricture

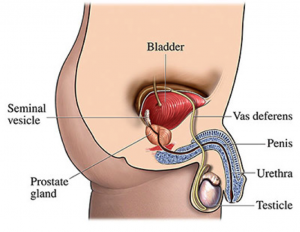

The urethra is the urine channel that carries urine and semen to outside. In men, it is about 20cm long. It consists of two main parts: posterior urethra, which is located in the pelvis and anterior urethra, which is located in the penis.

What is a urethral stricture?

A urethral stricture is a scar in or around the urethra, which can block the flow of urine, and is a result of inflammation, injury or infection.

Who is at risk for urethral strictures?

Urethral strictures are more common in men because their urethras are longer than those in women. Thus men’s urethras are more susceptible to disease or injury. A person is rarely born with urethral strictures and women rarely develop urethral strictures.

What are some causes of urethral stricture?

Stricture disease may occur anywhere from the bladder to the tip of the penis. The common causes of stricture are trauma to the urethra and infections such as sexually transmitted disease or damage from instrumentation. However, in some cases, no clear cause can be identified. Stricture of the posterior urethra is often caused by a urethral injury associated with a pelvic bone fracture (e.g., motor vehicle or industrial accident). Patients who sustain posterior urethral injuries from pelvic fracture generally suffer a disruption of the urethra, where the urethra is cut and separated. These patients are completely unable to urinate and must have a supra pubic tube (catheter) placed into the bladder to allow urine to drain until a repair can be performed. Trauma such as straddle injuries, direct trauma to the penis and catheterization or instrumentation can result in strictures of the anterior urethra. In adults, urethral strictures may occur after sexually transmitted diseases as gonorrhea, infection of the urethra, prostate surgery, instrumentation of urethra as during removal of urinary stones, urinary catheterization or other instrumentation.

What are the symptoms of urethral strictures?

Some symptoms that may be an indication of urethral strictures can include:

- Painful urination

- Slow urine stream

- decreased urine output

- spraying of the urine stream

- blood in the urine

- abdominal pain

- urethral discharge

- urinary tract infections in men

- infertility

How are urethral strictures diagnosed?

The urethra is like a garden hose. When there is a kink or narrowing along the hose, no matter how short or long, flow can be significantly reduced. When a stricture becomes narrow enough to decrease urine flow, the patient will develop symptoms. Frequent urination, urinary tract infections and inflammation or infections of the prostate and scrotal contents (epididymis) may occur. With long-term severe obstruction, damage to the kidneys can occur.

Evaluation of patients with urethral stricture disease includes a physical examination, urethral imaging (Retrograde urethrogram, voiding cystourethrogram), ultrasound) and urethroscopy.

The retrograde urethrogram is an invaluable test to evaluate the stricture: location and length. Both location and length are very important in order to plan surgical correction. The retrograde urethrogram is performed as an outpatient X-ray procedure and usually recommended to be performed by the reconstructive surgeon who will perform the operation. This study involves insertion of contrast dye (fluid that can be seen on an X-ray) into the urethra at the tip of the penis. No needles or catheters are used. The retrograde urethrogram study allows doctors to see the entire urethra and outlines the area of narrowing at the stricture. The patient is then asked to urinate and pictures are taken. This is called voiding cysto-urethrogram.

Urethroscopy is a procedure where the doctor gently places a small, flexible, lubricated telescope into the urethra and advances it to the stricture. This study permits the doctor to see the urethra between the tip of the penis and the stricture. All of these tests can be performed in an office setting and will allow the urologist to provide treatment recommendations.

In the case of urethral trauma, once emergency treatment has been provided, the evaluation of patients with posterior urethral disruptions involves a retrograde urethrogram, and if a suprapubic catheter is present, injection of contrast dye through this tube at the same time. Contrast injected from below fills the urethra up to the injured area, and contrast injected from above fills the bladder and the urethra down to the stricture. These two films together allow the surgeon to determine the gap between the two ends in order to plan the surgical repair.

How can urethral strictures be prevented?

The most important preventive measure is to avoid injury to the urethra and pelvis. Avoid unnecessary instrumentation or catheterization of urethra. Also, if a patient is performing self-catheterization they should exercise care, to liberally instill lubricating jelly into the urethra, and to use the smallest possible catheter necessary for the shortest period of time.

Acquired strictures may be a result of inflammation caused by sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Although gonorrhea was once the most common cause of inflammatory strictures antibiotic therapy has proven effective in reducing the number of resulting strictures. Chlamydia is now the more common cause, but strictures caused by this infection may be prevented by avoiding contact with infected individuals or by using condoms. When infection does occur, prompt and complete treatment of the STI with appropriate antibiotics will help prevent future problems.

What are some treatment options?

Treatment options for urethral stricture disease depends upon the length, location and degree of scar tissue associated with the stricture. Options include enlarging the stricture by gradual stretching (dilation), cutting the stricture with a laser or knife through a scope (urethrotomy) and surgical removal (excision) of the stricture with reconnection and reconstruction possibly with grafts or flaps.

Dilation :

This is usually performed in the urologist’s office under local anesthetic and involves stretching the stricture using progressively larger dilators called “sounds.” Alternatively, the stricture can be dilated with a special balloon on a catheter. Dilation is rarely a cure and needs to be periodically repeated. If the stricture recurs too rapidly the patient may be taught how to insert a catheter into the urethra periodically to prevent early closure.

Pain, bleeding and infection are the main problems associated with dilation procedures. Occasionally, a “false passage” or second urethral channel may be formed from traumatic passage of the “sound.”

Urethrotomy :

This procedure involves use of a specially designed cystoscope that is advanced along the urethra until the stricture is encountered. A knife blade or laser operating from the end of the cystoscope is then used to cut the stricture, creating a gap in the narrowing. A catheter may be placed into the urethra to hold the cleft open for a period of time after the procedure to allow healing in the open position. The suggested length of time for leaving a catheter tube draining after stricture treatment can vary.

Urethral Stent:

This procedure involves placement of a metallic stent that has the appearance of a circular chain link fence. The stent is placed into the urethra through the penis using a specially designed cystoscopic insertion tool after the urethra is widened. The stent expands within the widened stricture and prevents the urethra from closing. The lining of the urethra eventually covers the stent, which remains in place permanently.

Most experts in this field believe that metallic stents should be reserved very select strictures. They are associated with high risk of infection and re-stricture. Removal of these devices is very difficult and may result in a more significant stricture.

Open surgical urethral reconstruction :

Many different reconstructive procedures have been used to treat strictures, some of which require one or two operations. In general, these cases should be handled by reconstructive surgeon who is familiar with all techniques no single repair is appropriate for all situations. The choice of repair is influenced by the characteristics of the stricture (such as location, length and severity). Short urethral stricture, less then 2 cm are best handled by excision of the stricture and reconnect the two ends (anastomotic urethroplasty). When the stricture is long and this repair is not possible, tissue can be transferred to enlarge the segment to normal (substitution procedures).

Anastomotic Procedures :

These are usually reserved for short urethral strictures where the urethra can be reconnected after removing the stricture. This procedure involves a cut between the scrotum and rectum. . A small, soft catheter will be left in the penis for 10 to 21 days and removed after an X-ray is performed to ensure healing of the repair.

Substitution Procedures

-

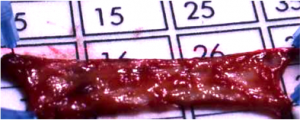

Free Graft Procedures:

Longer strictures may be repaired with a free graft procedure to enlarge the urethra. The most common graft used is buccal mucosa removed from inside the cheek. Brief hospitalization and catheterization for two or three weeks are usually required after this procedure.

- Skin Flap Procedures: When a long stricture is associated with severe scarring and a free graft would not survive, flaps of skin can be rotated from the penis to ensure survival of the newly created urethra. These procedures are complex and require a surgeon experienced in plastic surgery techniques. Brief hospitalization and catheterization for two or three weeks are usually required after this procedure.

- Staged Procedure: Occasionally When sufficient local tissue is not available for a skin flap procedure and local tissue factors are not suitable for a free graft, a staged procedure may be required. The first stage in a staged procedure focuses on opening the underside of the urethra to expose the complete length of the stricture. A graft is secured to the edges of the opened urethra and allowed to heal and mature over a period of three months to a year. During that time, patients urinate through a new opening behind the stricture, which in some cases will require the patient to sit down to urinate. The second stage is performed several months after the graft around the urethra has healed and is soft and flexible. At this stage the graft is formed into a tube and the urethra is returned to normal. A small, soft catheter will be left in the penis for 10 to 21 days.

What are the possibilities of recurrence?

Because urethral strictures can recur at any time after surgery, patients should be monitored by an urologist. After removal of the catheter, follow-up of the repair should be performed intermittently with physical examination and X-ray studies being performed as necessary. Sometimes, the doctor will perform urethroscopy to evaluate the repaired area. Some patients will have recurrence of stricture at the site of the prior repair. These are sometimes mild and require no intervention, but if they cause obstruction they can be treated with urethrotomy or dilation. A repeat open surgical repair may be needed for significant recurrent strictures.

Post urethra disruption

This is only seen after severe blunt trauma, usually motor vehicle accident or industrial injury. This is usually associated with fracture pelvis. There is complete disruption of the urethra, where the urethra is cut and separated. These patients are completely unable to urinate and must have a supra pubic tube (catheter) placed into the bladder to allow urine to drain until a repair can be performed.

Repair is performed after patient becomes stable, usually 6-8 weeks. The procedure can be very difficult and complex and requires surgeon with extensive experience.