Penile Deformities

The penis is a cylindrical organ consisting of three separate chambers. On the upper (dorsal) portion of the penis there are two corpora cavernosa that are surrounded by a tough but elastic layer of connective tissue called the tunica albuginea. The third chamber is called the corpus spongiosum; it is located below the corpora cavernosa and is surrounded by a thin connective tissue sheath. It contains the urethra, the narrow tube that carries urine and semen out of the body.

These three chambers are made up of highly specialized, sponge-like erectile tissue filled with thousands of venous cavities, spaces that contain very little blood when the penis is soft. During erection, blood fills these cavities, causing the corpora cavernosa to balloon and push against the tunica albuginea. While the penis hardens and stretches, the skin and connective tissue of the penis remain loose and elastic to accommodate the changes.

Deformity of the penis occurs when there is disproportion expansion of either both corpora cavernosa or corpora spongiosum resulting in either dorsal or ventral curvature or between both corpora cavernosa resulting in lateral curvature. It is usually apparent when the penis is erect.

There are two types of penile deformities

-Congenital penile deformity

-Aquired penile deformity

Congenital penile curvature:

This is a rare condition found in approximately 0.4/1000 men. Men with Congenital Penile curvature are born with a penis that is longer on one side than the other. Often the curvature is to the side but can be upward or downward. The penile length is usually very adequate and there is no plaque or scarring. It is usually apparent when the penis is erect, and is noticeable as soon as young men become sexually active. Most men are born with mild degree of curvature and the penis is bent downwards. However, in some cases, the curvature is severe enough to interfere with sexual intercourse.

Peyronie’s Disease

Peyronie’s Disease is an uncommon disabling deformity of the penis in which painful, hard plaques form underneath the skin of the penis leading to penile curvature and deformity. It affects about 0.388 to 1% of adult males It usually affects patient between 5th and 6th decade. Formation of fibrous plaque lead to shortening, curvature or constriction of the penis during erection. Although, Fallopius initially described this disease as early as 1561, most credit has been given to Francois da la Peyronie, a French physician who reported the first group of patients with fibrous cavernositis in 1743 in a paper titled ‘ Some obstacles Preventing normal ejaculation of semen [2]. ‘ He suggested that this condition was caused by irritation and could be successfully resolved by taking the water of Bareges in Southern France. Since that early description, extensive clinical and basic science research have been performed in an attempt to further understand the pathophysiology of this disease and investigate various medical and surgical therapy.

What is Peyronie’s disease?

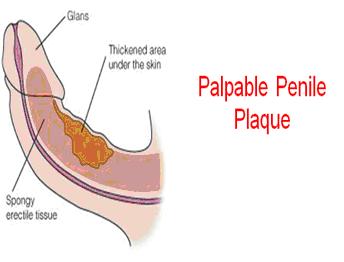

Peyronie’s disease (also known as indurations plastica penis) is an acquired inflammatory condition of the tunica albuginea of the penis. The principle manifestation of Peyronie’s disease is the formation of a scar tissue or hard plaque (a segment of flat scar tissue) within the tunica albuginea of the penis. This plaque can usually be felt through the penile skin. This plaque is not a tumor but it may lead to serious problems such as curved and/or painful erections. .

What are the symptoms of Peyronie’s disease?

The plaques of Peyronie’s disease most commonly develop on the upper (dorsal) side of the penis. Plaques reduce the elasticity of the tunica albuginea and may cause the penis to bend upwards during the process of erection. Although Peyronie’s plaques are most commonly located on the top of the penis, they may also occur on the bottom (ventral) or side (lateral) of the penis, causing a downward or sideways bend, respectively. Some men have more than one plaque, which may cause complex curvatures.

In some men an extensive plaque that goes all the way around the penis may develop. These plaques typically do not cause curvature but may cause a “waisting” or “bottleneck” deformity of the penile shaft. In other severe cases, the plaque may accumulate calcium and become very hard, almost like a bone. In addition to penile curvature, many patients also report shrinkage or shortening of their penis.

Since there is great variability in this condition, men with Peyronie’s disease may complain of a variety of symptoms. Penile curvature, lumps in the penis, painful erections, soft erections, and difficulty with penile penetration due to curvature are common concerns that bring men with Peyronie’s disease to see their doctors.

Peyronie’s disease can be a serious quality-of-life issue. Studies have shown that over 75% of men with Peyronie’s disease have stress related to the condition. Unfortunately, many men with Peyronie’s disease are embarrassed about the condition and choose to suffer in silence rather than speaking with their health care provider about it.

How common is Peyronie’s disease?

Recent demographic surveys have reported that Peyronie’s disease can be found in up to 9% of men between the ages of 40 and 70. The condition is rare in young men but has been reported in men in their 30s. The actual prevalence of Peyronie’s disease may be much higher than 9% due to patient embarrassment and limited reporting by physicians.

Interestingly, more Peyronie’s disease cases have been reported in recent years. This is likely due to the availability within the last decade of highly effective oral medications for the treatment of erectile dysfunction (ED). With more men seeking treatment for erectile problems, many cases of Peyronie’s disease that would have gone undiagnosed in the past have come to the attention of the medical establishment. It is likely that the number of men being treated for erectile dysfunction will continue to increase in the future. For this reason, the number of men presenting with Peyronie’s disease will likely continue to increase in the future.

What causes Peyronie’s disease?

Most experts believe that Peyronie’s disease is likely the consequence of a minor penile trauma. The most common source of this type of penile trauma is thought to be vigorous sexual activity (e.g., bending of the penis during penetration, pressure from a partner’s pubic bone, etc.) although injuries from sports or accidents may also play a role. Injury to the tunica albuginea may trigger a cascade of inflammatory and cellular events resulting in a process called fibrosis, a medical term for formation of excessive scar tissue. This abnormal scar tissue in turn forms the plaque of Peyronie’s disease.

Not all men who suffer occasional mild trauma to the penis develop Peyronie’s disease. For this reason, most researchers believe that there must be genetic or environmental factors that contribute to the formation of Peyronie’s disease plaques. Men with certain connective tissue disorders such as Dupuytren’s contractures and men who have a close relative with Peyronie’s disease have a greater risk of developing the condition. Certain health conditions such as diabetes, tobacco use, or a history of pelvic trauma may also lead to abnormal wound healing and may contribute to the development of Peyronie’s disease.

Peyronie’s disease is in essence a derangement of normal wound healing. Because it is related to normal wound healing, Peyronie’s disease is a very dynamic process early on but over time, the inflammatory changes may decrease. In fact, this disease is usually divided into two distinct stages. The first phase is the acute phase; this portion of the disease persists for six to 18 months and is usually characterized by pain, worsening penile curvature and formation of penile plaques. The second phase is the chronic phase where the deformity remains in a stable state. As in the first stage the deformity may interfere with sexual activity and there may be associated erectile dysfunction. Pain with erection usually improve or disappear during the chronic phase.

How is Peyronie’s disease diagnosed?

A physical examination by an experienced physician is usually sufficient to diagnose Peyronie’s disease. The hard plaques can usually be felt with or without erection. It may be necessary to induce an erection in the clinic for proper evaluation of the penile curvature; this is usually done by direct injection of a medication that causes penile erection. Pictures of the erect penis may also be useful in the evaluation of penile curvature. Penile Doppler ultrasound is very important to visualize the plaque, determine penile blood flow and the quality of erection.

How is Peyronie’s disease treated?

In about 13% of cases, Peyronie’s disease goes away without treatment. Many physicians recommend conservative (non-surgical) treatment for at least the first 12 months after symptoms present.

Men with small plaques, minimal penile curvature, no pain, and satisfactory sexual function do not require treatment. Men with active phase disease who do have one or more of the above problems may benefit from medical therapy. Unfortunately, very few well designed clinical trials of medications for Peyronie’s disease have been performed and therefore the true effectiveness of many of these treatments is unclear.

Oral Medications

Oral vitamin E: An antioxidant that is a popular treatment for acute stage Peyronie’s disease because of its mild side effects and low cost. While studies as far back as 1948 have demonstrated decreases in penile curvature and plaque size from vitamin E treatment, most of these studies have not used placebo controls. Those few studies of vitamin E that have included a placebo treatment group have demonstrated that vitamin E does not appear to give better results than the placebo, which calls into question whether or not vitamin E is an effective treatment.

Potassium amino-benzoate: Also known as Potaba®. Small placebo controlled studies have shown that this B-complex substance popular in Central Europe yields some benefits with respect to plaque size, but not curvature. Unfortunately, it is somewhat expensive and use of the medication requires taking 24 pills a day for three to six months. This medication has also been associated with a high rate of stomach upset, which leads many men to stop taking it.

Tamoxifen: This non-steroidal, anti-estrogen medication has been used in the treatment of desmoid tumors, a condition with properties similar to Peyronie’s disease. Unfortunately, placebo controlled trials of this drug are rare and the few that have been conducted have not shown that Tamoxifen is better than placebo.

Colchicine: An anti-inflammatory agent that decreases collagen development. Colchicine has been shown to be slightly beneficial in a few small, uncontrolled studies. Many patients taking colchicine over the long term develop gastrointestinal problems and must discontinue the drug early in treatment. It has not been proven to be superior to placebo.

Carnitine: An antioxidant medication that is designed to reduce inflammation and thereby decrease abnormal wound healing. Like many other Peyronie’s therapies, uncontrolled trials have demonstrated some benefit to this treatment but a recent controlled trial has not demonstrated it to be superior to placebo.

Trental (Pentoxifylline): This is a drug used primarly in patients with peripheral vascular disease. It has been shown to provide some relieve in patients with Peyroni’s disease and reduce the size of the plaque.

Penile Injections

Injecting a drug directly into the plaque of Peyronie’s disease is an attractive alternative to oral medications. Injection permits direct introduction of drugs into the plaque, permitting higher doses and more local effects. To improve patient comfort a local anesthetic is usually given prior to the injection.

Because plaque injection is a minimally invasive approach, it is a popular option amongst men with active phase disease and men who are reluctant to have surgery.

Verapamil Injections: Verapamil is a calcium channel blocker usually used in the treatment of high blood pressure. It has also been shown to disrupt collagen production and this property has made it of interest in the treatment of Peyronie’s disease. Several uncontrolled studies have suggested that verapamil injection is an effective treatment for penile pain and curvature; unfortunately, there are no large-scale placebo controlled trials of this treatment. Verapamil appears to be a reasonable and affordable treatment option for Peyronie’s disease, but further controlled studies are needed to verify the effectiveness of this treatment.

Interferon Injections: Interferon is a protein that is normally made in the body and plays an important role in inflammation. It has been shown to have anti-fibrotic effects in the treatment of keloid scars and scleroderma, a rare autoimmune disease affecting the body’s connective tissue. This effect is thought to occur by inhibition of collagen producing cells and by production of collagenase, an enzyme that breaks down collagen that has already been produced.

A large-scale placebo controlled trial of interferon injection for Peyronie’s disease was recently published. This trial demonstrated modestly better improvements in penile curvature, pain, and sexual function in men treated with interferon compared to those treated with placebo. While this is an encouraging result interferon is a relatively expensive treatment with flu-like syndrome side effects.

Collagenase Injections (Xiaflex) : Direct injection of the enzyme collagenase to break down the plaque of Peyronie’s disease has been a topic of interest among some researchers. A small trial from the early 1990’s demonstrated some modest improvements in Peyronie’s disease after treatment with collagenase injections. A larger trial is currently underway. The role of collagenase in the treatment of Peyronie’s disease is at this time unclear.

Other investigative therapies:

Many alternative methods for treating Peyronie’s disease have been reported. Examples include high-intensity focused ultrasound, radiation therapy, shock-wave treatment, topical verapamil, hyperthermia, and many others. While the scientific rationale for these other approaches is sound, at this time there is not enough data to support their use outside of a research setting at this time. A recent pilot study (2007) using external penile traction therapy demonstrated measured improvements in girth, length and curvature after 6 months of daily stretch therapy lasting from 2-8 hours per day.

Surgical Treatment of Peyronie’s Disease:

Surgery is reserved for men with severe, disabling penile deformities that prevent satisfactory sexual intercourse. Most physicians recommend avoiding surgery until the plaque and deformity have been stable and the patient pain-free for at least six months. An evaluation of the penile blood supply using injection of erection producing medications is often done prior to any surgery. A penile ultrasound may be performed at the same time. These two tests permit assessment of whether or not the man has significant ED and may also provide important anatomical information that will help guide the choice of surgical procedure. There are three general approaches to surgical correction of Peyronie’s disease:

Procedures that shorten the side of the penis opposite the plaque/curvature

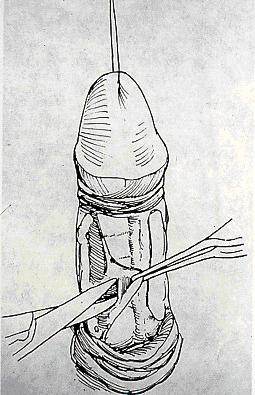

These procedures are generally safe, technically easy, and carry a low risk of complications such as bleeding or worsening erectile function. One particular disadvantage of these approaches is that they tend to be associated with some loss of penile length. For this reason shortening procedures are generally preferred in men with mild or no ED, mild to moderate curvatures, and long penises. Examples of this type of procedure include the Nesbit procedure, in which small pieces of tunica tissue are excised from the convex (the side opposite the direction of the curvature) side of the penis. The edges of the tunica are then sewed together, causing penile straightening. This procedure is rarely used and has been widely replaced by other variations including the 16 dot penile plication, in which sutures are used to “cinch” (or bunch) together a segment of the tunica on the convex side of the penis.

Procedures that lengthen the side of the penis that is curved

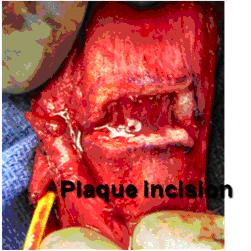

These procedures are indicated when the curvature is severe or there is significant indentation causing a hinge-effect or buckling of the penis due to the narrowed segment in the penile shaft. In these cases, the surgeon incises (cuts) the plaque to release tension. In some cases a segment of the plaque may be removed. After the plaque has been incised, the resulting hole in the tunica must be filled with a graft.

These procedures can correct severe curvatures, in most cases without significant shortening of the penis. Unfortunately, this type of procedure is technically challenging and carries a risk of worsening erectile function. Therefore, lengthening/grafting procedures are typically not recommended except in cases of severe deformity in men with adequate erectile function at baseline.

A number of different materials are available as grafts and the choice of graft should be based on patient and surgeon preference. Autologous tissue grafts: These grafts are made of tissue taken from another part of the patient’s body during surgery. Examples of grafts used for Peyronie’s disease include saphenous vein (taken from leg) and temporalis fascia (harvested from behind the ear). Autologous grafts are living tissue and generally incorporate into surgical sites much more readily than some other materials. Disadvantages of autologous grafts include the need for a second incision to harvest the graft.

Non-autologous allografts: These grafts are sheets of tissue that are commercially produced using human or animal sources. Prior to use they are sterilized and processed to remove all potentially infectious particles. These grafts are gradually digested by the body but they serve as scaffolds for the growth of fresh healthy tissues produced by the patient’s own body. Allografts are uniformly strong, easy to work with and readily available because they are “off-the-shelf” in the operating room. They are generally well tolerated by most patients and negate the need for a second incision although they are somewhat expensive.

Synthetic inert substances: Materials such as Dacron® mesh or GORE-TEX® are seldom used for Peyronie’s surgeries in the modern era. When used as a tunical grafts these substances often cause significant recurrent fibrosis and hence worsening of Peyronie’s type deformities.

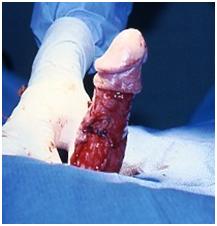

Placement of penile prosthetic devices

Placement of an inflatable penile pump or malleable silicone rods inside the corpora is a good treatment option for men with Peyronie’s disease and moderate to severe erectile dysfunction. In most cases,implanting such a device alone will straighten the penis, correcting its rigidity. When device placement alone does not sufficiently straighten the penis, the surgeon may further straighten the penis by cracking the plaque against the rigidprosthesis or by incising the plaque and subsequently covering the incision with a graft material.

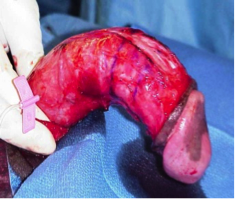

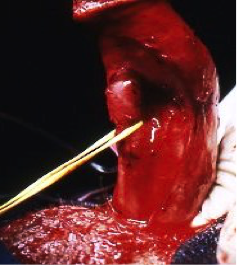

Dissection of neurovascular bundle

Plaque incision

Venous graft

What can be expected after surgery for Peyronie’s disease?

A light pressure dressing is typically left on the penis for 24 to 72 hours after the surgery to prevent bleeding and hold the repair in place. In some cases, patients will wake up with a catheter in the bladder but this is usually removed in the recovery room. Most patients are discharged later the same day or the following morning. The patient is also often given several days of antibiotics to reduce the risk of infection and inflammation and a pain medication for discomfort. In most cases surgeons recommend not engaging in sexual activity for at least 4-6 weeks after surgery, longer in some cases of complex repairs.

Frequently asked questions:

What happens at the molecular level following penile trauma?

Following any penile trauma, injured cells release a veritable stew of chemical messengers that have a number of important effects, including the activation of fibroblasts, cells that produce connective tissue. Normally these cells produce organized collagen sheets that restore the normal architecture of the penis. Some fibroblasts transform into cells called myofibroblasts, cells that not only produce collagen but also contract to help bring wound edges together. Myofibroblasts are designed to do their job and then die off. However, in some cases, fibroblasts produce abnormal, disorganized collagen and myofibroblasts do not die, leading to persistent wound contraction and inflammation. These two processes lead to overgrowth of dense scar tissue, which in some cases becomes the plaque of Peyronie’s disease.

Are men with Peyronie’s disease prone to any other conditions?

About 30 percent of men with Peyronie’s disease develop fibrosis in other areas of the body. The most common sites are the hands and feet. Dupuytren’s contracture is a condition classically associated with Peyronie’s disease in which fibrosis occurs in the tissue of the palm. Dupuytren’s contracture may lead to progressive permanent bending of the fingers. While the fibrotic process in Peyronie’s disease and Dupuytren’s contracture is similar, it is not clear at this time what causes either plaque to develop and why men with Peyronie’s disease are more likely to develop Dupuytren’s contracture.

Does Peyronie’s disease turn into cancer?

Cells obtained from Peyronie’s plaques have shown a number of characteristics similar to cancer cells, such as the ability to resist a process of programmed cell death called apoptosis, and to form tumors when transplanted into mice with no immune systems. However, there has never been a case of Peyronie’s disease that has turned into a cancer in a human. However, if your doctor observes other findings that are not typical with this disease—such as external bleeding, obstructed urination, or prolonged severe penile pain—he or she may elect to perform a biopsy on the tissue for pathological examination.

What are the most important things to know about Peyronie’s disease?

Peyronie’s disease is a poorly understood urological condition characterized by penile deformity and pain. Treatment for this condition needs to be individualized to each patient based on the timing and severity of the disease. The objective of any treatment should be to reduce pain, normalize penile anatomy so that intercourse is comfortable, and restore erectile function in patients who suffer from concomitant erectile dysfunction. The early phase of the disease is treated with either oral medications and/or plaque injections approaches. Traction therapy is emerging as a potential valuable non-surgical treatment. The late phase of the disease is usually managed with surgery if penile deformity is preventing a man from enjoying sex. As medical researchers continue to develop basic and clinical research for a better understanding of this disease, more therapies and targets for intervention will become available.